When attitudes become - curating.

The 747 was born out of the explosion of the popularity

of air travel in the 1960s. The enormous popularity of the Boeing 707

had revolutionized long distance travel in the world, and had began the

concept of the "global village" made possible by jet revolution.

The first edition of the jet, the 747-100, rolled out of the new Everett

facility on 2 September 1969. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeing_747)

In 1969 Playboy magazine printed an interview with Marshal McLuhan in

entitled "A Candid Conversation with the High Priest of Popcult and

Metaphysician of Media," pp. 53-74, in The Essential McLuhan, Eric

McLuhan and Frank Zingrone (ed.), (New York: Basic Books, 1995)

When attitudes become form, March - April 1969 1969, Suisse, Berne, Kunsthalle,

curator: Harald SZEEMANN.

As a child, an impressive day was when we drove to the airport Zurich. Nobody was dropped off or picked up. We couldn't even imagine flying since we didn't know anybody living beyond 30 minutes driving. We went to see the first jumbo jet, the Boing 747, which left the factory in 1969 and was flying first for PanAm in 1970. On that occasion, we went on to visit a newly built shopping center outside Zurich next to the high way, another novelty in the early 1970s. Our family never entered a museum, nor any bookshop or library.

"When attitudes become form" was an exhibition that wouldn't

have been possible without the jet revolution. Harald Szeemann was working

for Kunsthalle Berne and had traveled the USA where he got to see contemporary

American art. This new art was already made by artists who had started

to travel by airplane and were mobile. This mobility changed not only

society but also art. I believe that conceptual art was the first 747

art form to facture transportation and mobility into material decision-making.

Marshal McLuhan's the-medium-is-the-message conversion soon dominates

all conversations that defined art: language and concept related works

emerged and artists started to communicate. Thought it was Karl Marx who

first discussed machines and tools as extensions of human organs and the

human body, McLuhan reworked it for a happily communicating and mass consuming

"global village" in which everybody potentially conversed with

everybody with no specific regards to relations of production and class.

A new area of national, racial and sexual liberations and emancipations

took off. The birth control pill, live TV-field-broadcasting, portable

and affordable video cameras, early computers and consumer electronics

rendering the world fun and promiscuous before the oil crisis, aids and

terrorism doomed the arena. The Munich 1972 Olympic terror attack coincided

with the beginning of live TV field-journalism broadcasting with mobile

cameras outside TV-studios. Artists and intellectuals also celebrated

this new world. They entered the field with propositions and international

exhibitions independent of museums and galleries. Ausstellungsmacher -

exhibition makers - became welcome and necessary to sort out existing

disorders and create new ones. Harld Szeemann called his office "Büro

für geistige Gastarbeit" - Office for intellectual guest work

- recycling the German term Gastarbeit usually reserved only for the then

new phenomenon of unskilled migrant industrial workers in Western Europe.

Gastarbeiter were and have been (even after generations) perceived as

foreign with only modest help for integration. Capital, work, services

and products traveled and exchanged and art as always tried to keep up

with the pace. Today, curators too are more often then not free agents

not directly associated with an institution. Szeemann himself has been

defining his role as a free agent even though there have been lose but

steady institutional associations. The same is true with many other well

known contemporary curators who might be employed by a museum or a Kunsthalle

but are perceived as independent and ready to be hired for any show anywhere

in the world if the context is attractive - i.e. reputation and remuneration).

Today, the internationalized system of art has become so complex and sophisticated

that any role can be taken on by any player anywhere in the game. We more

and more see now also artists collecting, curating, writing and dealing

as well as collectors, writers and curators making art and reflecting

about artistic production in the role of writers and art historians. Interesting

enough, even Harald Szeemann, and not only Hans-Ulrich Obrist couldn't

resist taking on the role of artists: He showed in the Tirana Biennial

2003, where he had some silk-screens made. Another example of mixing roles

is this text which was commissioned by Victor Misiano, a trained art historian

who turned curator, publisher, critic and director of an art center. ("I

am deputy director of the State Center for Museums and Exhibitions. I

am editing my Moscow Art Magazine. I am curating, publishing. writing

and so on") Misiano commissions me, an artist, to write a text on

how to teach curating. He doesn't ask me for an artwork, he asked me for

a pedagogical essay.

It can't be pointed out enough that these changes are the product of a

dramatically changing society and its permanently improving technologies.

Therefore any other domain changes as well. I give here only three basic

unrelated examples but which artists and curators have come to reflect

upon. Banking: I pay now with money I don't have and make financial transaction

with the computer and the mobile phone. I shift virtual money - a euphemism

for my debts - from credit card to credit cards and feel lured into debts.

I have started to believe that my extending credit frame is my actual

money. Food: I call in for food, or I take it out, I freeze it and microwave

it. I also complement it with highly processed vitamins, proteins and

whatever I think I need that doesn't often resemble anything "eatable"

or "natural". I also cook myself with easy to follow instructions

and pre-prepared substances. Needless to say that parts of my foot is

now manipulated, designed in size, resistance, taste and composition.

I came recently to realize that often in one bite I have products from

three to four different continents. Yet, another basic activity that undergoes

drastic change is work: Today, we work at home, we work in teams via computers

without seeing each other, we work three jobs and more at the same time.

We chose, we outsource and subcontract parts and entire productions and

work in multiple places around the world simultaneously with our digital

arms, voices, eyes and brains.

Is it therefore a surprise that I - in the role of an artist - make my

curators paint my paintings, my dealers do my drawings and part of my

artistic decision-making. Here at home, I study Chinese and Arabic, I

write texts, I try to sell my art, and I panic to organize money, recuperate

debts from others, curate shows, advice dealers. I even collect some art.

Currently, there are up to 20 people producing my artistic work for me

in different places, different continents for different shows with different

financial support. It is partially done by people who are no artists and

don't understand it. If my computer is an interface, I am an "interbrain,"

a decision-making body which is processing and producing information.

In this new, twisted and multi-layered international context, curators

have to create and not only find their own niche. They have to work locally

as well as internationally. Some local positioning comes almost automatically

with international exposure. Getting a show or curating a show even in

upcoming Brooklyn galleries - so let's even ignore Chelsea or London's

East End - will be noticed in mayor art centers around the globe with

the speed of spam. On the other hand, any international exposure today

is barely reaching a larger audience then any traditional local community

since the grandiose art world of today is thinned out to a tiny suburb

in a village. A minority of highly specialized professionals that communicates

across borders in a new audio-visual Latin backed by a fast changing theoretical

jargon starts to vitally interact from the moment new members enter graduate

classes in fancy international art schools. Art-star teachers, often not

longer out of school then their students in school, integrate quickly

new artists into a tide network of contacts. They smoothly mingle with

curators, and writers in the many international events available, first

as volunteers and interns, then as curators and artists. Many public event

providers who love to act internationally offer now "residential

programs," and indoor or outdoor experiments for curating and art

making. European countries see in their cultural spheres national and

chauvinistic pride without ignoring the fact that museums and cultural

activities are promotional keynotes for their local tourist industries

as well as for their real estate sectors. This allows for a very active

exchange between all cultural participants on an international level.

Grants are the passwords for this international exposure.

Recently, curating has not only become internationalized but also institutionalized

and turned into a discipline that is taught academically. International

classes for curatorial learning are now created anywhere: at universities,

art schools, museums, auction houses and so on. The question of "What

to teach curators?" is about as impossible to answer as "What

to teach artists?" in a time of deskilling and artistic outsourcing.

I am convinced that the recipe for a good curator is the same as for somebody

who succeeds in life and anywhere else. It is an elixir that I locate

in people themselves. It is the basic understanding of who we are, of

where we are from, of how we are living, of what we want, and of what

we can do. This "che voi?" (Italian: "What do you want?"

Lacan) is crucial in shielding us from things other people want us to

want, to do, to buy, to believe, to sell, to say and to fight for. Concerning

art and artist, I don't really have any preference as long as I can see

that there is a genuine interest in what a person is doing, an interest

that is not opportunistic, externally driven and remote controlled by

trends and dominating taste formations. Curators too, should learn to

distinguish between motivations and interests that are intrinsic and logical

to those that are not. On top of that they have to figure out what kind

of art they would like to defend, for whom, and why. They also have to

find inventive ways to put their vision respectfully into practice without

the total exploitation of artist and anybody else helping in the making

of a show.

Everybody should have answers to the questions of why they do what they

do. These answers should be intrinsic to the job and not extrinsic to

it. Money, power, and banking love shouldn't dominate curatorial or artistic

decision making though it can never be avoided. But we all know people

who are purely motivated by the social context onto which they project

themselves without any authentic interest in what they do. Many are those

curators who only work with the view artists from high-powered galleries

with already guaranteed status. This reinforces the given artistic and

curatorial status quo without challenging it - sometimes without even

comprehending it. Curators should not only understand artists, be able

to listen to them but should also understand their own role in today's

constant remaking of a complex cultural and political landscape. Anything

we visitors, collectors, curators, artists, and dealers do is part of

on an ongoing eternal shaping and reshaping of esthetic, cultural and

intellectual standards that have wider political, social and ideological

impacts. Cultural and intellectual formations can be liberating or oppressive

and have wide repercussions on individual psychologies but also on general

politics. Right now, in the post-9/11 period in the United States, cultural

institutions and universities are under more pressure to be complicit

with right wing politics and encourage a terrifying culture of mutual

mistrust and eavesdropping. Critical departments lose their funding, political

speech is discouraged and intimidated, artists are threatened with lawsuits,

and independent media outlets risk being silenced. It has been so far

impossible for a group that resisted the war against Iraq to purchase

advertising space at Time Square denouncing war. Currently there are several

lawsuits opened against artists and I could be one of them given "my"

US-postal stamp-project that plays with symbolic civil disobedience (www.ganahl.info/cuchifritos.html).

Today, everybody has to understand that he/she is part of a larger discourse

shaping our public and private spheres in a less oppressive way.

Years ago, I happened to be part of the Whitney Museum Independent Study

Program (ISP) that puts artists, curators and writers together in a course

for professionals expected to succeed somehow in the highly competitive

field of cultural production. During that formational year, we worked

together without much discussing art and the usual politics that surrounds

it. Art seemed almost a taboo that was better addressed in the back rooms

and corridors than in the regular and frequent plenum discussions. We

were expected to read books, and had to work through non-ending photocopies

of articles relevant to discussion on the cultural front. Art was only

one optical device to look outside our windows. In many ways, it did change

my way of thinking and doing things, for not saying that it actually changed

the direction of my life. This wasn't the case because of social contacts

made during that program but because of what we discussed, what we read,

what we focused on. I found subsequently a way to reformulate my art making

and thinking that can be partially traced back to the two years I spent

there. A couple of years later, I was invited to Grenoble where a curatorial

"école" was created. When the ICP program didn't provide

any means and was only equipped with a photocopy machine, the Le Magasin

in France offered grants, travel stipends and all kind of other possibilities

still unavailable to the NY based program. To my surprise, in France,

nobody was interested in art or any subject I proposed to discuss. The

talk was only about "How did you get your book published," "How

do you get in there" etc. Traveling and social networking were privileged

over reading and discussing culturally important issues.

Lets now look at the question of power for some of these relevant cultural

agents. As I have pointed out earlier, cultural roles are becoming more

diversified, more difficult to define and somehow interchangeable in this

always changing landscape. Yet, this doesn't indicate that the power and

influence inherent to these roles is evaporating. If artists curate a

show or collect art they create the same effects on the distribution of

power and influence than when "curators-only" or "collectors-only"

do it. As an artist, I have had quite some troubling experiences with

artist-curators. Some of them have assumed the power of curators but not

the responsibilities of curating. During the selection process they were

reasoning like curators but during the organizational phase they acted

like artists: i.e. paying little respect to artist's work. Artists have

the right to see the world through their works and are allowed to deal

with their art works in whatever way they decide. But when in the role

of a curator, they have to change their optics and need to respect other

artist and their works. Of course, people who are professional curators-only

can act irresponsibly as well.I am going now to be very specific and polemical

and use samples of my own experience, positive and negative ones. I might

risk consternation on both ends: There are many curators I have had the

pleasure and honor to work with excellent and positive outcomes then I

can list here. Also, generally speaking, I have been treated by most curators

with respect, intelligence and generosity. Of course, the experiences

on the other end of the spectrum have been disappointing but relatively

minimal. Pointing to a few cases where things went wrong might add a bitter

taste to this essay when reading it. But it hasn't disenchanted me: Quite

the opposite. I have learned to understand that behind these conflicts

- that can take on very personal and idiosyncratic forms - there are mostly

structural problems traceable back to weak financial support due to greedy

communities that host these institutions. For the few negative cases I

have created web-pages that feature the exact development and context,

and show key correspondences.

My worst experience ever so far has been with Italian curator Claudia

Zanfi who has been trying to disown me of an artwork of mine using quite

intricate tactics to do so. We are still in dispute since my piece has

not been returned. This case is documented to the point that is almost

amounts to a sociological study of a town (www.ganahl.info/sassuolo_txt.html)

and serves as an example of an entire network of exploitation and self-exploitation

in the middle of a rich city that refuses to give enough money to the

arts in spite of its attempt to recycle it for its image. The curator

Zanfi made herself a complicit agent in this mechanism of disrespect and

abuse. Maike Pollack from Southfirst gallery in Brooklyn is another case

of somebody who tried to extort artworks from me and even kicked me out

of the running group show I was in (www.ganahl.info/stamped.html). Ad

midst some minor cases of frustrations which I'm listening here in the

hope of pressuring some solutions thanks to the power of free speech,

I have to mention well-known Italian artist Maurizio Mnannunci who heads

a respected art space in Florence entitled BASE. After three years of

empty promises, he still hasn't yet reimbursed me the promised airfare

nor returned my art works. The other petty case that isn't even worth

a description here can be seen on line with some artists-curators based

in Amsterdam (www.ganahl.info/arti.html) who did me in financially and

on the level of presentation. My last remarkably disappointing example

in curating with a large and respected institution had been with Christian

Bernard who invited me to do a one-person show in a part of the Mamco

in Geneva in 1997. Though funding was guaranteed and a time for the opening

was chosen, the show was abruptly canceled for rather ludicrous reasons

only 2 months before its scheduled opening. No rescheduling. In place

of my show, Bernard put the work of an artist who much more smoothly fit

the social network context of the rest of the artists then occupying his

chic museum. In that case, it wasn't money or financial support that provoked

the conflict though Bernard used the funding-argument as a pretext. He

had my written assurance that all costs were covered by resources others

than his.

Before I go into positive territory of my best experiences with curators

and museum programmers, I would like to address the funding issue, a permanent

source of potential conflict. There are artists who reject participation

when there is no funding, when they have to pay themselves. I do not share

this position and differentiate. I sometimes participate even when I have

to pay myself. But I have learned to insist that funding is discussed

in a clear and comprehensive way upfront. Years ago, I accepted the no-funding

conditions of the Contemporary Art Center Moscow when Victor Misiano was

curator. At that time there was no money in Moscow and Misiano made it

clear from the beginning. I organized myself, went ahead and had a great

time. I was able to produce a show I organized around the studies of Basic

Russian and my Reading Seminar projects. This exhibition has been important

for my own working-history and the lack of international reception and

funding didn't matter.

Currently, I'm working on a one-person exhibition for a non-for profit

space in Hong Kong, Artist Commune, which requires elaborate work. The

chief curator Shin-Yi Yang, who is currently in a PHD-program at an Ivey

League school here in the USA, invites a guest curator, Mie Iwasuki who

invites me. The show sounds great but there is also no funding. He simply

seems to ignore the fact that we are on the other side of the globe. It

was made clear that there is no money. I accept it because several volunteers,

including both curators will study with me Chinese on a regular basis

advancing my four-year old Basic Chinese art project. Mie Iwasuki is hard

working and supportive. Additional to teaching Chinese, she is painting

three large canvases for my show. I will pay my own flight ticket, cover

the costs of most of the materials and hope to have a nice time in Hongkong.

Without making it look like a complaint I can't ignore the fundamental

question why a rich city like Hong Kong can't afford basic coverage of

artistic activities? Why do curators work when there is no financial support

for the arts? Answers are complex but always comprehensive within the

logic of pre-monetary thinking that dominates the art world. My "I

don't sell but I learn something"-mantra undergoes in this case a

slight modification.Currently, I am in another international situation

with no funding that is acceptable and pleasant. It is an intelligent

show that doesn't require any money. They understand that internationalism

doesn't necessarily have to signify air travel and jet lag. Alejandro

Cesarco and Gabriela Forcadell are curating a show - if we are allowed

to call it that - for the Centro Cultural Rojas without any significant

funds but lots of engagement, ideas and pleasure. At least, Cesarco is

living permanently in Brooklyn and acts as a satellite decision maker

to the Argentineans, still hard hit by the failed politics of the IMF

and the World Bank. I am one of the artists invited every month to present

a bibliography to read with an introduction explaining the artist's selection

of texts with proposed reading strategies. The texts go into an archive

they are about to set up in remote and cash poor Argentina. There seem

to be lots of people left with curiosity and interest for art and artists'

reasoning. For me, this participation is not only a perfect pretext for

reading but also a way to brush up the link between my fingers and some

parts of my cortex. I love to express myself with old-fashioned media

that have been dominating me and my artistic rendering: reading, writing

and discussions have been the center pieces in many of my exhibitions.

These basic cultural practices have become more and more anachronistic

in a cultural status quo that works with mice, scrolling bars, clicks

and remote control sticks. Seeing these curators - who are mainly artists

who don't like to wait around - working respectfully with simple and eco-friendly

strategies makes me almost forget about the stress that can define this

world of programming.

Next to money, there are many other conflicts like we know them in daily

life. I am going to pick here only a few that become more and more apparent

between curators and artists: Artistic interference by curators. It is

the result of changing roles and the deskilling in many artistic practices.

Curators start to interfere and compete with artists in the artistic decision

making process: "Make it bigger, make it smaller, use this material

etc...." Curators also assume roles that resemble prior demands by

Maecenas and other patrons. "We want you to do a bar, a dance floor,

a skateboard ramp, wall paper, furniture, a floating structure, and last

but not least a tomb for the CEO." The merging of artistic production

with the emergence of a small artistic cottage industry of social services

reinforces this kind of interference as well. "Could you a reading

seminar? Will you teach the children of the neighborhood? Will you psychoanalyze

members from our museum board?" Because artists are today often producers

and organizers of their own art works and don't shy away from spectacle

and event planning, their modes of working and managing affairs have become

similar, if not the same to those of curators or dealers. This proximity

between curators and artists is therefore a lure that everybody should

be aware of.

The importance of ("I wonna get mass-") media attention in the

art world is yet another factor that can push artists and curators onto

crashing courses. People compete for public and narcissistic love. Attention

seems to be the lifeblood for our media driven industry. It is not uncommon

that curators of mega-shows are more important than the art temporarily

left behind by an international jet set. When Harald Szeemann invited

me for the Kwangju Biennial in 1997, the Korean press couldn't stop asking

questions about my star curator. "How is it working with him? How

did he find you? Have you worked with him before? What do you think about

Szeemann? Etc..." Almost no substantial question about my artistic

proposition was asked. Today, many writers follow this obsession with

curating and curators. Larger group shows don't seem to fall or stand

with the work of the artists in the show but with the curatorial reasoning

placing it. Unfortunately, this selection process can often resemble horse

betting or stock picking contests. People prefer seeing reoccurring high

profile names mixed with unknown young newcomers. Older artists try to

rejuvenate themselves through collaborations with young talents. Curators

reinvent themselves by inviting younger artists. They easily can change

their modes of working and synchronize their perception with the flux

of things.

It is no surprise that thinking about art in scores and ranking proliferates

since even investment capital enters the arena. Without knowing many details,

it came to my attention that some high profile US-curators are not only

advisors but founders of a venture fund amassing capital to invest in

the arts. With auction prizes of contemporary art exceeding even the appreciations

of internet-stocks during the frantic years of irrational exuberance,

it is no surprise that institutionalized investment thinking has become

a reality. By the way, published best selling lists in business magazines

of artists have been around since the 1980s. I sometimes have the feeling

that many curators of museums make exhibitions to impress and signal to

other curators and directors of museums advised by blue chip galleries

and collecting board members. The "shopping" of artists is defining

museum profiles. At the peak of their careers, highly overbooked and overexposed

players move from big museum to big museum only. It is not an easy game

to assure the booking of these high-flying artists. This gives the false

impression that there is such a think like the NBA of art.

But there isn't. More often then not, when artists touch a certain critical

point of success and exposure they start to over-produce and under-perform.

I am inclined to say that museum shows that don't challenge artists, curators,

the public and critics are prerecorded visual musak. We all shouldn't

ignore the common fact that most artists become known for works they did

when few people expressed interest in them and when barely anybody was

spending money on them. In this landscape of illusions, endless diversity

and competitive selecting, decision-making is difficult and contextualizes

curators quickly. "Who do you show? Who do you collect?" Curators

stay and fall with their artists, their galleries, their openings, their

dinner invitations, and their press coverage. Working with famous artists

brings fame to curating (and vice-versa).

I finally resume with the giving of names of people who have offered me

opportunities for one-person shows at moments when the discrepancy between

my recognition as an artist and the importance of the inviting institution

was huge. At the time of my invitation, these curators were in positions

of power and could have shown artists who commanded much higher social

consensus and approval rates than I did. Risking to disappoint important

curators and supporters of mine who for simply technical reasons can't

be mentioned all, I am thanking here the following people who all gave

me one person museum shows: Annegreth Nill, Dallas Museum of Art, 1992;

Timothy Blum, Person's Weekend Museum, Tokyo, 1993; Sabine Breitwieser,

Generali Foundation, Vienna, 1997; Edelbert Köb, Kunsthaus Bregenz,

1998; Each of these curators and directors had open and endless options

for their programming but were choosing me because of my artistic work

only. None of these choices were influenced by social dynamics and networking

power games. There had been no dealer or other match-maker involved. My

status as a relatively unknown artist allowed me to take each of these

shows very seriously. For these museums, I was able to make shows that

have become important for my own art making. Each show has somehow altered

my artistic direction and turned into a crucial corner stone for the developing

of my artwork. Interesting enough, almost all of these shows were relatively

ignored by critics, by other institutions and by collectors. I just received

an invitation by Bill Kaizen to make a one-person show at Wallach Gallery,

the Columbia University Museum in 2005. This is a well-funded institution

that usually limits itself to historical positions only. Again, I am amazed

that this curator and doctorate student in art history has made me his

choice diverting from the regularly prescribed path of his respected institution.

I'm concluding this essay with the banality of stating that there is no

formula to teach neither artists nor curators. Every success story differs

and cannot be replicated or even fully understood. To a certain degree,

it is nearly impossible to decide what success means for people involved:

Busy schedules? Frequent Flier Gold Memberships? Sales? Visitors? Prestigious

institutions? Media coverage? Artistic consistency? For my part, I define

successful stories those that require redefinitions of the very notion

of success. My heart is with curators who sometimes against all odds are

dedicated to a certain artists, or certain aesthetics without landing

social or critical success. I don't even have to like them very much.

In New York, Kenny Schachter has been one of these cases for a long time

that are difficult to define. Next to a curator he is also a lawyer, a

collector, an artist, a writer, a dealer, a gallery owner and recently

a real estate developer. Many of the artists that have come to be meaningful

and recognized in the 1990s had been first showing in Schachter's rather

chaotic events that were placed in unconventional spaces. His frequent

programming was held in empty non-art spaces across downtown Manhattan

were shows were as much visited as criticized. Most of his artists really

hadn't shown before. But quite a number of them moved on with desirable

and profitable careers, some ignoring Schachter in their biographies.

I liked only a handful of artists he had worked with over the years. I

couldn't appreciate the majority of his aesthetics choices, but I very

much recognize and adore the fact that he has been home to many artists

he showed and collected early on, anticipating and shaping major visual

trends in New York. For my personal understanding, Schaechter redefined

and extended the social role of the artist/curator/writer/collector/dealer/entrepreneur

in a way to remember and to shock.

I end abruptly with the unsatisfying feeling that much had been left out.

Being exposed to art and artists is an endless school that is in no need

for teachers or students. Listening to artists should be the most urgent

job of anybody who works or pretends to work for the arts. Good artists

and good curators find their own way to defy the dull institutionalization

and the non-stop commercialization of art and its vital channels of communication.

They are not satisfied with art schools or curatorial training courses,

with dealers and museum directors, with the market and state sponsored

event cultures for chauvinistic or group-narcissistic ends. The same applies

also to an intelligent audience and outstanding collectors who appreciate

and dedicate themselves to things they really like themselves. All these

participants know that they need art in their struggle to live a decent

and meaning full life. In today's international world of total marketing,

spam comes also in form of cultural products we don't want, don't need,

and don't (want to) understand. Today, the responsibility of everybody

involved with the endless process of a cultural and artistic production

and mediation is bigger then ever before. It is a sublime endgame to be

endlessly continued on a glocal level. In order to return to the beginning

of this essay I would like to point out that Fedex, e-mail and the internet

have made even jet-traveling non-essential for being active on the narrow

broadband of a temporal globalizing presence. Since everything seems just

a keyboard away the choices of staying or flying, curating or art making,

consuming or ignoring cultures become not more than an attitude in non-ending

changing world.

Rainer Ganahl New York , July 2004

(unedited text)

PS1: PS1-Moma is amidst many other things not only a sold out program

for artists - it basically is now history since the 12 months program

is cut down to a meaningless three months period that will only produce

"paid exhibitions" (I was told by current participants that

contributing countries are asked to pay 30.000 dollar for 3 months) -

but also a sweatshop for curators and its dancing public in Brooklyn.

I feel like I didn't point out enough that responsibilities in curatorial

decision-making are very important and shouldn't be exported beyond political

thinking. I really feel that if we are not careful enough we risk waking

up on a page of George Orwell with the only difference of wearing better

clothes and seeing in four colors. We might be asked to take off our shoes

not only before boarding a plane but also when "turning corners"

in our cities.

PS2: A careful critical reader/friend of this text has correctly pointed

out that sketches about the "post-Marxist" classless global

village have not been taken up again. He is right. If I look at the provenience

of the most successful recruitments of the “cultured class”

in the USA (Europe will see more of that as well), one cannot ignore the

fact that the politics of private schooling and universities is paying

well off. Successful curators, artists or writers are more and more an

exception and a thing of the past. That is in particular also true with

the very slow but yet happening integration of so-called minorities. They

might be African-American or immigrants of Pakistani, Latino or Chinese

decent but they most likely come from rather wealthy families. Structural

economic divisions on the consuming end of highbrow culture – independent

of whether artworks address popular audiences or speak with the vernacular

of popular culture – are even more determining. The trend to even

facture cultural production as well as consumption into the demarcation

line of class divisions is increasing and can be observed everywhere,

from advertising to real estate planning, from educational investments

to on line dating. Curators should be very much aware of what they are

doing in regard to the accelerating discrepancies within the disappearing

middle classes.

PS3: It goes without saying that I am deeply indebted to and appreciative

of everybody who has worked with me in whatever role. I feel very sorry

that this text does not allow me to name every single person. My text

would have been 20 more pages long. But I do want to mention two people

here in New York who have been and are still tremendously supportive and

generous with me: Devon Dikeou, artist, writer, curator, collector and

editor of zingmagazine and Manfred Baumgartner who is offering me a third

one person exhibition in New York where the killing cost structure is

so high that an exhibition with an artist of my commercial track record

doesn't look justifiable - another curatorial choice against the grain.

PS4: I did not elaborate on the disputes that still are driggering on thought people keep promsing to return works and to pay - the reality until this date has been different and still frustrating. But I do offer links with most of the communications where I clearlyl layout the dispute that is for everybody nothing but a headache. I therefore ask anybody to look at these web pages in case somebody is interested in details. I ommitted these details because it is not the topic of this text.

BELOW some IMAGE choices for possible ILLUSTRATION:

HI RES IMAGES FORf Reading Seminars : IMPORTED -- 1993 - 97

HI RES IMAGE FOR READING FRANTZ FANON

HI RES IMAGES FOR READING GRAMSCI

My First 500 Hours Basic Chinese, 1999- 2001 (Museum Ludwig, Cologne)

250 video tapes of 120 min in 50 boxes, 500 video

click image to download hi res image

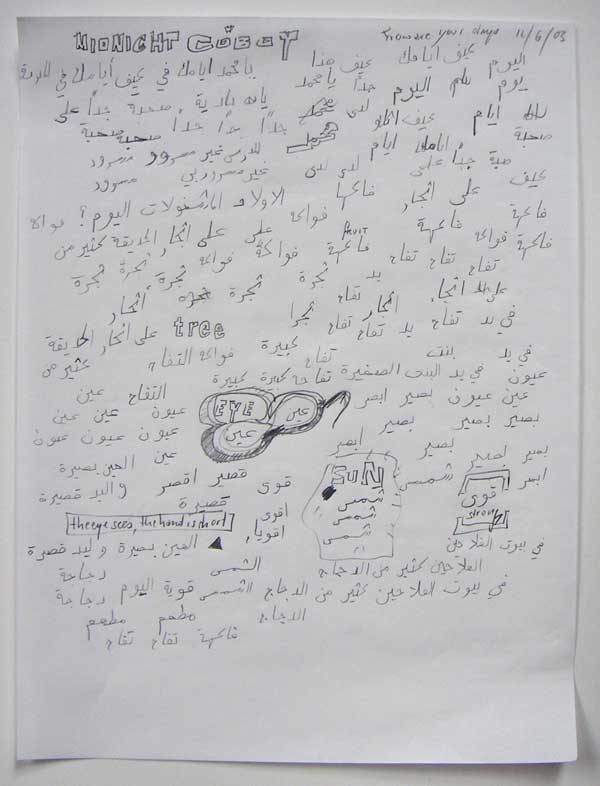

Basic Arabic (Study Sheet), 12/6/03 New York

(work on paper, 9 x 12 inches)

click image to download hi res image

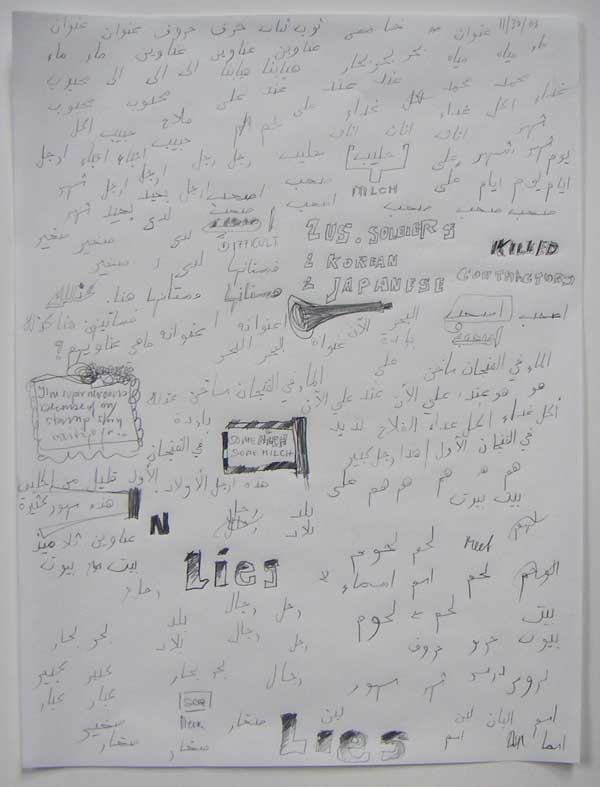

Basic Arabic (Study Sheet), 11/30/03 New York

(work on paper, 9 x 12 inches)

click image to download hi res image

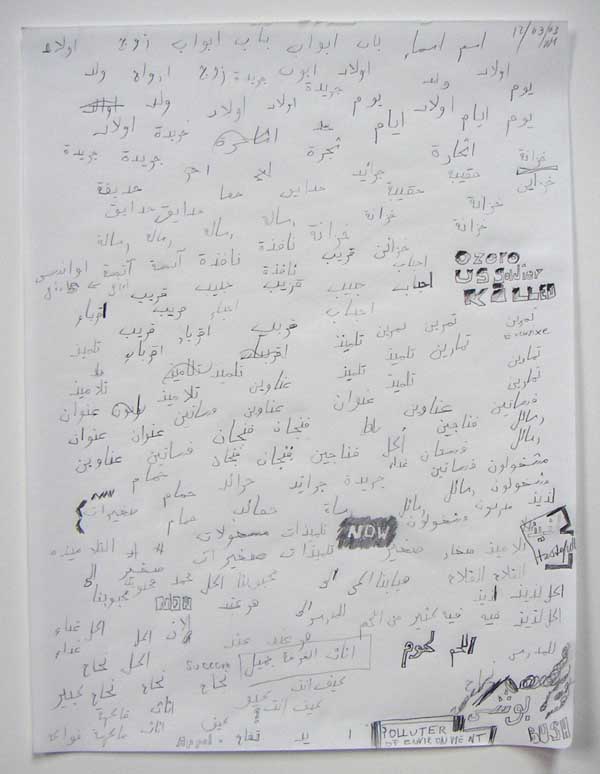

Basic Arabic (Study Sheet), 12/03/03 New York

(work on paper, 9 x 12 inches)

click image to download hi res image

click image to download hi res image

Rainer Ganahl

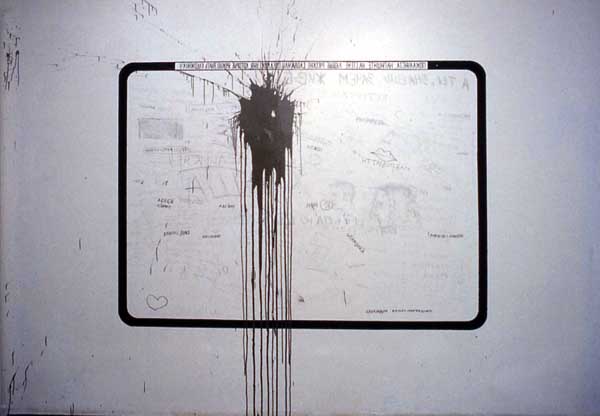

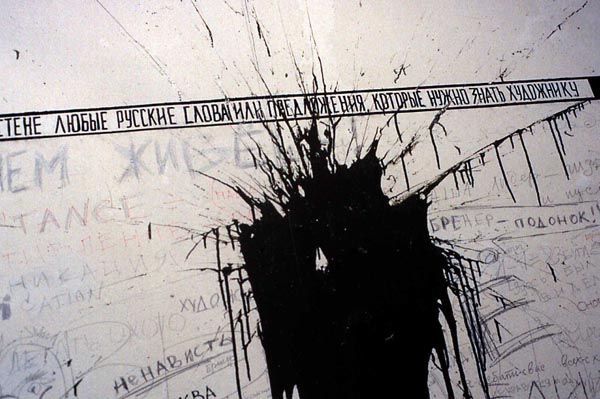

Please, write down the Russian words the artist should should know,1995

interactive wall painting with different responses in different media.

This work was part of my show at the Contemporary Art Center Moscow in 1995. At that time of the shows, I offered this conceptual piece for free to Joseph Backstein (director of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Moscow). Backstein was about to put together a collection of contemporary art in Russia he simply refused my offer. I was surprised since I offered it for free. Backstein, a writer, curator, collector, philosopher and empressario of cultural events diidn't want it. Since it was a piece that could be stored in form of a photograph, a reconstruction diagram and a certificate of authenticity I was really wondering. Today, I am not offering it anymore for free. Since this is the first publication of this piece I would like to thank everybody who contributed to this dialogical work with their writing - and their paint throwing.

click image to download hi res image

click image to download hi res image

more picutres coming soon