written in German - see German text >> - thanks to Margaret Ewing for translating this text for me!

“Imagine there is war and nobody shows up?”

War makes me sick!

War is escalating as I sit here trying to write something, though completely

ignorant on the subject. War reports – as “headline news”

– are a constant element of the media design of our environment.

On the radio and internet, in the newspaper and on television, they take

on a quasi-decorative function. War reports run next to advertisements,

shopping, entertainment, and a hundred other bits of information and distraction

(“infostractions”), and are released and sold by a few large

agencies – Reuters, Associated Press – nonstop, like on an

assembly line. Just now the situation in Lebanon is escalating, and its

airport has been bombed by Israel. (BBC, NYC Radio, Yahoo News, derstandard.at).

Yesterday’s newspaper published disaster photos from Mumbai of nearly

200 dead. (New York Times). I also read there that in the last 3 days

in Iraq there have been over 100 killed. The constant killing in Sudan

and in other regions of the world doesn’t make the news or headlines

right now. Furthermore, the deliberations and defacto preparations for

a preventative war against North Korea (Japan’s politicians and

defense minister are in agreement with this as of last week) and Iran

are forced into the background, although this changes the situation only

slightly.

I feel sick.

I belong to the generations of Europeans who have no direct experience

of war. (No European wants to admit that the war and genocide in Yugoslavia

actually took place in Europe.) The current escalation in Lebanon could

theoretically have directly affected me when I visited this region two

years ago – something that further drives my ideas on the subject.

I also have plenty of friends here in NY whose relatives live in Haifa.

I experienced the destruction of the World Trade Center with my own eyes.

It still felt very abstract and unreal, even though I know quite a few

people who lost friends in this catastrophe and I had to inhale dirty

toxic air for a month and developed breathing problems. Based on worried

questions and discussions with Europeans and Americans who don’t

live here, it seems to me as if the destruction of the Twin Towers was

experienced for a longer time and more intensely than by those who were

here in the city. This has also been confirmed by all of the post-9/11

polls about the estimation of danger, the level of fear, and the desired

response in America. It is in this discrepancy between direct and imagined

experience that I see the power of the media over our ability to imagine.

The media plays a part in creating reality as it transforms an abstract

scene into pictures that feel like something personally experienced. When

I was in Moscow in 1991 (Yeltsin crisis, siege of parliament) protesting

with Russians between the tanks, I felt like a protagonist in a déjà-vu

soap opera, and so felt relatively secure, even though quite a few protesters

were shot nearby on the same night.

I know war only from the media and from the personal reports of people

who were affected. I remember, for example, a young Kosovar artist from

London, who I came across three years ago on the beach in Albania. In

response to my questions about war, he explained to me that he and three

friends from London flew to Kosovo voluntarily to participate in the war,

in order to defend his people. He was the only one who survived. That

took my breath away. I couldn’t ask anything further – I didn’t

want to know anymore. An oppressive feeling of shame and guilt mingled

with the heat of the day. I sensed that behind all these unimaginable

destructions called war that constantly surround us via impressive, aestheticized

photographs and reports, was a gaping banality that insignificantly, unrestrained,

and senselessly feeds the realm of the escalation of violence.

In the 60s and early 70s the two world wars were a matter of curious questions

and selective answers and accounts within the family, and were hardly

brought up in my schools. (My question to my father, “Did you shoot,

too?,” still remains unanswered, although his silence and the shrapnel

in his neck and skull are a kind of answer.) As children we could also

play in the ruins and old ditches of the wars, where we hid and even kissed.

Munitions shells and things from the attic like medals, pieces of uniforms,

duffel bags, shoes, and Reichsmarks were our toys. We also saw many people

with wartime disabilities, for whom we gave up our seats on the streetcar,

ahead of pregnant women, the blind, and the elderly. In the 70s and 80s

the threat of a nuclear winter hung over all of us like a real and unreal

ghost. In “London Calling,” The Clash sang about “nuclear

fear.” This ambivalent real-unreal aspect of the so-called Cold

War was part of a personal deep-rooted feeling. As a nihilistic teenager

with only an immediate short-lived sense of time, I was sure that I wouldn’t

make it to 30, having already lost my mother and brother prematurely (which

was attributed to the indirect psychological longterm effects of the Second

World War.) War would destroy us all.

My grandparents had survived two world wars, and my parents one, and their

memories and accounts – as well as the media – were not totally

wasted on us, but were rather compartmentalized into a part of our minds.

To us children, these world wars seemed very monumental and historically

overwhelming, and seemed to have been sent from God. Grandmother sometimes

took us to pray that another war would not break out. The war took on

a meteorological-theological quality, like a thunderstorm sent from God.

In Vorarlberg I felt geopolitically secure. The mountains seemed to offer

protection from atomic attacks, and there were no significant targets

in the immediate area. The mountains did not, however, protect us from

the radioactive fallout of the heavy clouds from Chernobyl, that quietly,

normally, harmfully, and inconceivably banally moved over the Alps. We

were unprepared for and unprotected against the rain that followed the

nuclear reactor disaster, and it brought countless numbers to their deaths.

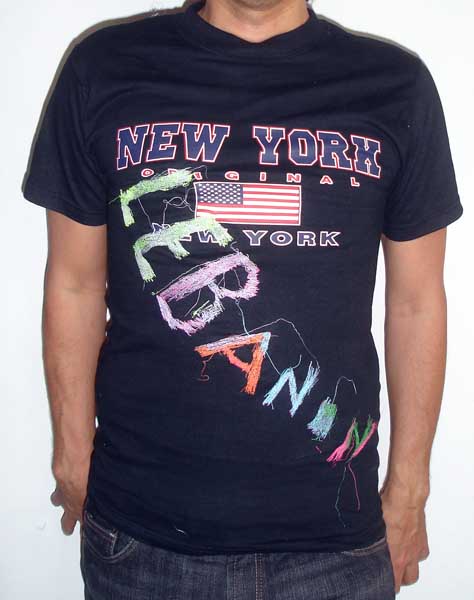

This year’s dominant atmosphere of disarmament and peace movements

turned me into a confirmed pacifist. People protested and wore t-shirts,

bandanas, stickers, and buttons about peace and disarmament. People hitchhiked

to protest rallies, marches, and peace concerts in Germany, Italy, and

Switzerland. A famous quotation circulated in many forms, that was (perhaps

falsely) attributed to Bertold Brecht: “Imagine there is war and

nobody shows up.” I think it was also a subject for essays in German

schools. I was surprised to learn from Google just now, that this quotation,

which was so frequently printed on posters, was actually incomplete, and

that it has a deceptive ending that would dash the pacifist’s hopes:

“Imagine there is war and nobody shows up. Then the war comes to

you.” This ending, which contradicted the goals of pacifism, astonished

me. Without soldiers the war battlefield should stay empty, and war could

not continue on, and also not come to us. If a soldierless war came to

us, this would mean that the pacifist solution would not be preventing

war, but rather subtly calling for a mobilization for war. This would

make this solution of refusing to go to war pointless.

Today we can see that the complete quotation can also be understood literally,

and that battlefields can exist without soldiers. There is technology

where destruction can be programmed on a screen, and armies are replaced

by non-military outsourcing to semi-privatized special units. Soldierless

battlefields can also arise where unresolved political conflicts are unevenly

manifested, and gym bags and suicide bombs bring death and misery to packed

restaurants, commuter trains, subways, theaters, and outdoor markets.

It seems to me that battlefields have increasingly disappeared –

that is, spread out – over whole regions and halfcontinents. According

to the reactionary theoretician Samuel Huntington, whole cultures and

civilizations will turn into war scenes. Furthermore, troops are no longer

necessary, and no soldiers need to be there.

The media brings the war to our living rooms and desktops in an instant.

The hopeful solution of not going to war mutates into the question, “What

would happen if there was a war and nobody looked?” Or more specifically,

“What happens when we see the onscreen headlines but don’t

click on them?” All of us at least look at the computer and the

“headline news.” Thanks to sensitive technology, these news

currents track our internet activity. Whether or not we notice it, every

hit and site visit is counted, registered, analyzed, and turned into user

profiles. Without intending to, one runs the risk of landing on a site

that propagates radical content of every kind. The Big Brother from “1984”

lives on in 2006, within a large family with innumerable siblings that

take on every conceivable form, in a logarithmic nightmare and mathematical

butterfly effect. As we know, the State Department demanded search data

from Google and other search engines, in order to be able to create a

picture of the interests of many millions of users. There is war, and

if you look, you will be observed. It is surely a subtle form of self-censorship

and paranoia when I say that I don’t dare to follow all online links

and to study sinister news sources. (There are secret no-fly lists to

screen for potential riskgroups. Meanwhile we have found out that all

telephone conversations in the USA were being analyzed.)

I look in spite of the depressing global situation, though I must say

that I find it overtaxing. Looking, clicking, and navigating supplement

my newspaper subscription. With the click of the mouse, I can get the

radio programs from various international stations around the world, acoustically

rounding out my worldview through the Infopipeline. It is striking to

notice that there are hardly any differences between reports from Germany,

Austria, France, England, Japan, and the USA, not only in their presentation,

illustration, and time of release, but also in their interpretation. Perhaps

this is due to the fact that the original reports come from just a few

sources. War wants to be looked at, to be listened to. What we call terrorism

can’t exist without cameras and reporting. War and terrorism, terrorism

and war, become cut out and shaped for an international news audience.

U.S. citizens hardly see any U.S. casualties, and even fewer wounded soldiers.

The world is full of complicated interests and conflicts, and should not

be characterized as a fairytale. We have recently seen how cartoons themselves

can trigger violence, and trigger their own war scenes. An accurate description

of war involves not only the numbers of bombs and deaths, but also many

other kinds of representation. It is not surprising that journalists and

entire television networks are always coming under fire. They have become

another battlefield. Pictures follow bombs and bombs follow pictures.

In the post-Watergate era, this means “follow the money.”

This advice is also crucial in the study of violence and its causes. Americans

understand the business of money and the quick worldwide transfer of money

very well. They understand even better its power to finance, directly

and indirectly, their political, ideological, economic, and social interests

worldwide. The makeup of the current Bush administration corresponds more

or less to the makeup of the most important sectors of today’s global

economy: petrochemical and pharmaceutical industries, financial sectors,

and not least the military industrial complex. Interestingly enough, this

government lacks a representative of the so-called new technologies, a

field often associated with the tender age, liberal background, and diversity

of the main protagonist. These megainterests and concentrations of power

seem to function as bridgeheads in today’s war scenes and theaters

of conflict.

But the money and power also follow the pictures. Power, money, and pictures

go together just like war and interests. Knowledge and power, resources

and violence. The interesting difference between “Follow the money”

and “Follow the pictures” is that while money drains from

our pockets in the form of taxes, high prices, state robbery, corruption,

etc, pictures come to us. Pictures and misleading explanations also come

to us without us asking for them, wanted or only estimated. The unbalanced

trade of money, power, and the demands of powerful monopolies for pictures,

calculations, and lies has also become a billion dollar business. The

former Prime Minister Berlusconi, the most facelifted and richest man

in Italy who gave Bush complete apriori support for the war in Iraq, controls

the majority of the Italian media, and tailored laws like shirts for his

own purposes. The corresponding pictures followed.

Power and money determine how war is delivered to us, through either celebrations

of or publication bans against inadvertent pictures. Images of war are

therefore loaded with money, gods, and power, as well as pictures, ideologies,

and interests. Soldiers are secondary. There is much more to not going

to war: not paying, not believing, not participating in commerce, not

looking, not listening, not wanting, not consuming. But the war comes

right to us – is flung onto the population. Everyone is involved,

whether on the frontlines or at home, wearing a helmet or supposedly safe

from the weapons of death and destruction. During the Vietnam War (probably

after the death of Martin Luther King), they said that every bomb that

fell on Vietnam also exploded in an American city (“innercity”).

Today international terrorism illustrates these words again and again

(London, New York…).

The miniaturization of every kind of technology and weapons system (pocket-sized

laser guided weapons) and the global demographic changes and revolution

in transportation of the last 40 years have made every capital into a

reflection of the world’s population, turning the Niebelungenlied

dream of absolute invulnerability into fantasy. Mandated conflict resolution

has also changed the situation, so that absolutely clear military dominance

is increasingly an illusion. (The “mission accomplished” in

Iraq is an example.) After barely two weeks of fighting, the Israeli army

must realize their miscalculations, since Lebanon’s air attacks

have not been reduced 50% as expected. They are dealing with an enemy

that has not only Iranian weapons systems at its disposal, but also modern

Chinese rockets, with which they succeeded in destroying a ship at sea.

Meanwhile here in the U.S., the media discusses this as a “proxy

war” – as connected to a war between the USA and Iran (what

a nightmare!), with its potential to spread across the region. Fasten

your seatbelts!

The utopian hope that one could somehow snatch the war, gods, pictures,

bombs, and rockets out of the sky mingles with melancholic aporia, political

powerlessness, and confused hatred toward all the decisionmakers. What

is missing in that hope is at least some sense of complicity in every

war, resulting from our dependence on and benefit from the acquisition

of raw materials and other western hegemonic claims. We drive cars and

fly on planes and use tvs, computers, air conditioners, and other energy

guzzling comforts. Much of our clothing, equipment, food, and drinks –

even water – travel constantly across continents and seas, the associated

costs of which we don’t pay directly. I’m surprised that nature

itself, global warming, and glacial melting are not considered terrorists

and part of the “axis of evil”. Nature is a great protagonist

that is rarely provoked by arrogant unilateral decisions. The consequences,

however, are already terrorizing us.

The provocative question, “Imagine, there is war and…”

is not some underrated crazy idea, but rather one that must be further

considered in your absurd-utopian, quasi-poetic, crazy artist ideas!

Imagine if today’s wars – for example Israeli, Lebanese, or

Palestinian – were fought without weapons, uranium-enriched rockets,

helicopters, suicide bombers, and homemade- or Iranian-supplied projectiles,

and instead only with hands!

Imagine if the media could only publish stories and marathon runners!

Imagine if the U.S. media published not only the numbers of dead Arabs

and Afghanis, but also the 2,500 killed and 19,000 wounded American soldiers

in Iraq!

Imagine if the true costs of war and consumption were passed on to the

consumer!

Imagine if military strategists were bicycle-riding artists with knowledge

of Arabic and Chinese, without direct links to lobby groups!

Imagine if peace negotiations were carried out not with the arrogance

of military supremacy, but rather with respect for the opposing side’s

vulnerability!

Imagine if at least half of the consumers who think oil prices are too

high were to organize daily protests in Washington and London!

Imagine if Sudan were as important as the western powers, and if every

time a village was liquidated the prices of all goods rose one cent!

Imagine if the religious- and media-driven fears of the masses dried up,

like the advancing evaporation and devastation of global warming that

creates new conflicts.

Imagine if world trade would be negotiated liberally, mutually, and justly,

and if interests and wealth were distributed equally instead of being

greedily concentrated!

Imagine if the absurd repetition of these quasi-dadaist demands for peace

would disgrace people into protesting in the streets against weapons!

Imagine if the ideas of poetic dreams, of spoiled urban alternatives and

the readers of this awkward essay would have a defacto effect on today’s

politics!

Imagine if people begin to grasp that different thinking stands in dialectical

relation to different action!

Imagine if the residents of New York, Washington, Los Angeles, and a hundred

other American and European cities would pour out of their homes and into

the streets like they did during the last power failure, and protest against

the universal prevailing war policy!

Imagine…

Rainer Ganahl

New York, July 24, 2006

www. ganahl.info

translation: Margaret Ewing

see German text >> -